1. INTRODUCTION

The phenomenon of limited access to financial services is a major challenge to the development of low-income people in the developing world who seek out ways to improve their livelihoods (Kono and Takahashi 2010). Africa has remained the most financially underdeveloped continent despite recent improvements in economic performance (Allen, Otchere, and Senbet 2011). Estimates from the World Bank suggest that while extreme poverty levels have declined, rapid population expansion has actually caused the number of people living in extreme poverty to rise from 288 to 398 million between 1990 and 2012 (Beegle et al. 2016). With Africa being the only continent not to have achieved the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of halving extreme poverty by 2015 (United Nations 2015), more attention and new strategies including microfinance revamp are needed if the continent is to achieve the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of eradicating poverty by 2030.

Microfinance institutions (MFIs) play a central role in enabling access to financial services for the poor; facilitating entrepreneurship, and driving general economic development (Ahmed-Karim, Alders-Sheya, and Sluijs 2015). Microfinance has been widely seen as an effective tool for poverty alleviation and women empowerment (Khan, Shaorong, and Ullah 2018). The rapid development of the sector has led to increased investments, increased competition among financial firms, and the development and sale of complex financial products (home mortgage loans) through information technology. However, the use of these sophisticated financial products remains limited and the rate of financial literacy continues to lag behind the pace of financial product development (Lusardi and Mitchell 2009), hence, consumers’ inability to understand and utilise these complex financial products. In addition, rapid changes in technology (use of mobile phones in financial service delivery) raises concerns over the type of protection needed by financial consumers on issues of disclosure, safety and education, especially for first-time users.

Client Protection Principles (CPPs) are a set of measures put in place by MFIs, regulatory agencies and government to ensure that the interest and investments of consumers are protected. CPPs enhance the financial bottom line and is imperative for business ethics (Perez-Rocha et al. 2014). Consumer protection helps to build demand and strengthen business standards, thus contributing to improving MFI governance. Some level of regulation is necessary to help protect the rights of consumers. The role of regulation in ensuring the proper and efficient functioning of financial markets is critical in protecting client investments and compensating losers (Benston 1999; Arun and Murinde 2008). Regulation is shown to have an effect on the outreach and social protection goals of MFIs in Africa. In addition, client protection is relevant for MFI sustainability and outreach, sound and stable financial market functioning, and gives new clients confidence in the financial system.

Despite the importance, issues of consumer protection and financial literacy remain a challenge (Rutledge 2010). Client protection remains weak particularly in developing economies where the vast majority of customers do not have a clear understanding of financial contracts to engage in meaningful negotiations with financial institutions. In addition, agencies meant to champion client protection issues either do not exist, or are frustrated by lack of clear-cut mandate. Organizational inefficiency and resource inadequacy are other reasons why championing client protection becomes herculean. Weak regulatory regimes and the absence of microfinance laws to regulate the sector have also contributed tremendously to the exploitation of clients with some resorting to suicide when their condition becomes unbearable (e.g. Andhra Pradesh, India; Mader 2013). No doubt the sector has come under serious public scrutiny for the complexity and diversity created by growth, increased calls for transparency and accountability and rising client over-indebtedness (Schicks 2013; Ahmed-Karim, Alders-Sheya, and Sluijs 2015). MFI transparency in Sub-Saharan Africa is reported to be low and variable (Tadele, Roberts, and Whiting 2018). These unhealthy incidents culminate in the development and implementation of CPPs aimed at creating more awareness on the rights of clients and the need to protect them in the financial service delivery space. However, little assessment if any has been done to ascertain the level of implementation of CPPs and the emerging gaps. This article, therefore, seeks to bridge this gap by evaluating the implementation of CPPs in Africa, and explore ways in which the microfinance sector can be moved towards better clients’ protection. In this regard, sector regulation and client awareness education are imperative. This study makes an empirical contribution to the literature, and the methodology used draws heavily from five practitioner papers purposively selected from the SEEP Network country-support publications. This has been complemented with previous research publications on client protection and regulation. Selection of the case study countries was based on data availability.

The study found that only few research efforts have been directed towards analysing the level of implementation of CPPs in Africa. High information asymmetries exist to the disadvantage of microfinance clients. Mechanisms for resolving clients’ complaints, fair and respectful treatment of clients, privacy of client data, and transparency in pricing are areas that require serious improvements. The study, therefore, makes a contribution to the literature by systematically reviewing CPPs in the case studies.

2. GROWTH IN MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS’ OUTREACH

Outreach is defined as the number of poor clients reached with financial services by MFIs and how these services meet their needs. The expansion and rapid growth in the microfinance sector have largely been attributed to the innovative lending approaches (group lending with joint liability) used by MFIs and the continuous neglect by formal banks to serve poor clients due to the perceived high risks associated with dealing such segments. Institutional diversification and the development and application of communication technologies in reaching out to poor and marginalised clients in rural areas have also facilitated microfinance outreach (Galema, Lensink, and Spierdijk 2009; Hermes, Lensink, and Meesters 2011). New banking technologies such as the use of cell phones and the Internet have improved MFI sustainability and efficiency (Hermes, Lensink, and Meesters 2011). These sophisticated technologies, though good in enabling access, has led to concerns over issues of consumer protection over time which requires more careful attention. However, research remains limited in this direction probably due to the overemphasis on MFI sustainability and impact.

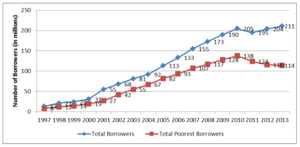

Figure 1 shows that, as at December 12, 2013, over 211 million poor clients had been reached globally with financial services by more than 3,700 MFIs, out of which over 54 percent were among the poorest clients (“Microfinance Summit Campaign Report” 2014). In terms of scale, the number of savers and borrowers, and the value of loan portfolios have increased exponentially. Between 2002 and 2007, a steady growth of 14 percent per annum was recorded in both the total number of borrowers and poorest borrowers. For the last five years, the total number of borrowers grew by 2 percent per annum while the number of poorest clients declined by the same margin (“Microfinance Summit Campaign Report” 2014). The peak outreach of MFIs occurred in 2010 after the global financial crisis of 2008. This suggests that the crisis had minimal adverse effects on the outreach goal of MFIs. Another view is that, the effects of the financial crisis have a time lag. In view of the burgeoning outreach of the MFI model, recent concerns are centred on client protection and the need for regulation.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, total reported client outreach now stands at over 12.6 million clients. However, 80 percent of the population still lack access to financial services, and their unmet demand is equally high (CGAP and MIX 2012; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Morduch 2009). Despite increasing outreach, the quality of growth remains a major concern to various stakeholders due to the higher interest rate charged by MFIs, client over-indebtedness, abusive debt collection practices and collateral seizures which do not only violate clients’ rights but undermine human dignity and threaten financial sector stabilisation. For instance, Khan, Shaorong, and Ullah (2018) found that MFIs neither reach the core poor nor empower women due to commercialisation that has led to a shift in focus towards more secure and profitable advances. Meyer (2019) revealed that outreach measures are associated with increased operating expenses. MFIs with a high share of rural borrowers find it difficult to exploit economies of scale and productivity effects (Lopez and Winkler 2018). In this regard, client protection and regulation has gained deep roots in the policy agenda and financial inclusion efforts in Africa. The fast-growing, unregulated microfinance sector has negatively affected MFI profitability and portfolio quality due to client over-indebtedness (the inability of borrowers to repay their loans). The overall growth rate of assets is reported to have declined from a peak of 45 percent in 2007 to 15 percent in 2008 (Lutzenkirchen and Weistroffer 2012). These and many other developments compelled some experts to question the effectiveness of the microfinance model as a development tool for poverty reduction (Bateman 2011). Nonetheless, microfinance is creating an impact in the lives of many and there is need to regulate the sector and protect the interest of clients.

3. THEORY OF CONSUMER PROTECTION IN MICROFINANCE

Several theories and models of consumer protection regulation exist in the economic literature based on neoclassical economic principles which are relevant in microfinance. Theoretical analysis of how consumers behave and the reasons for their actions underlie the behavioural models of consumer protection. This theory is based on assumptions regarding what consumers will do and the reasons for their actions. Consumers maximise expected utility as a function of price and quality of the services. Quality is reflected in safe and effective financial service delivery. However, relevant knowledge is yet to be found and many doubt if it will ever be found due to the complex nature of human behaviour. One drawback of the theory is that it gives very little information regarding consumer reactions to packaging and truth-in-lending disclosures and their actual views on warranties (Shapo 1974). Also, consumer rationality has some cognitive limitations as pointed out by recent studies on behavioural economics (Campbell et al. 2010; Thaler and Sunstein 2008).

The consumer behaviour theory has some implications. Firstly, quality levels differ, and based on the level of information, some consumers may underestimate the quality differences. Controlling for clients’ preferences, perceptions, and service use thus remains a significant problem facing financial institutions. The accuracy of client perceptions is a key factor in the consumer protection theory which is complex and difficult to estimate accurately. Secondly, increase in financial product sophistication, the rise in consumer expectations, and rising complexities in consumer constraint are characteristic of most financial markets. Current legislation and modern investments respond to product problems with difficulties, hence, there is an urgent need for adequate information and improved competition in microfinance markets.

Economic models of consumer behaviour are rooted in the idea of utility maximisation. The approach posits that consumers are rational in their decision making and are able to weigh the satisfaction to be derived from all available goods in relation to each dollar spent. This, though relevant in microfinance, has limited application due to unequal knowledge of information among actors. Demand and supply factors in the market greatly influence issues of client protection in microfinance. Benston (2000) examined six regulatory goals[1] and the findings revealed that capital regulation is useful in ensuring a reliable supply of financial services. However, financial services-specific regulations are unnecessary and undesirable for the other goals.

Government regulation of financial service providers and products is based on maintaining consumer confidence in the financial system and ensuring the optimal use of financial services. However, several mechanisms such as structured early warning interventions exist which financial institutions could utilise to maintain client confidence in the financial system. The failure of microfinance markets to protect clients provides the basis for regulation aimed at helping to ensure fairness, transparency and sector development. Lessons from failed development projects and formal financial institutions create doubts about public support for unregulated MFIs. For instance, failure of savings groups in China due to abscondment of group leaders with members’ savings reduces public confidence in microfinance (Tsai 2000). In Uganda, unscrupulous lenders capitalised on unregulated microfinance markets to steal from clients with such resultant implications on the microfinance sector as diminishing future borrowing and clients moving away from microfinance (Duggan 2016, 205). Inadequate regulation and supervision have been widely recognised as potential problems in the sector, however, enforcement of microfinance laws to regulate the sector remains low in Africa. Effective monitoring and supervision by local financial authorities/agencies is a challenge, and issues of client protection often fall outside of the scope of monitoring effort (Ahmed-Karim, Alders-Sheya, and Sluijs 2015). However, public interest in the sector is growing and regulation is crucial for better client protection.

Advocates of the microfinance model need to promote client protection and the role of MFIs in fostering modern enterprise development. As noted by Karnani (2009), romanticising the poor as value-conscious consumers has led to underemphasis on the legal, regulatory and social mechanisms that protect them. While legislation alone may not overcome issues of client protection in the sector, MFIs need to be more proactive, innovative, and to develop adaptive financial and non-financial services that promote ethical practices.

4. CLIENT PROTECTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PRINCIPLES

Consumer protection encompasses the responsibility that other stakeholders have to ensure transparency and fair treatment of customers across the entire microfinance market. Both client protection and consumer protection concepts are used interchangeably in this study. They are aimed at protecting clients against unethical practices and ensuring that dignity, fairness, and sound market practices prevail. Regulation could help moderate the actions of various players and offer protection to vulnerable consumers.

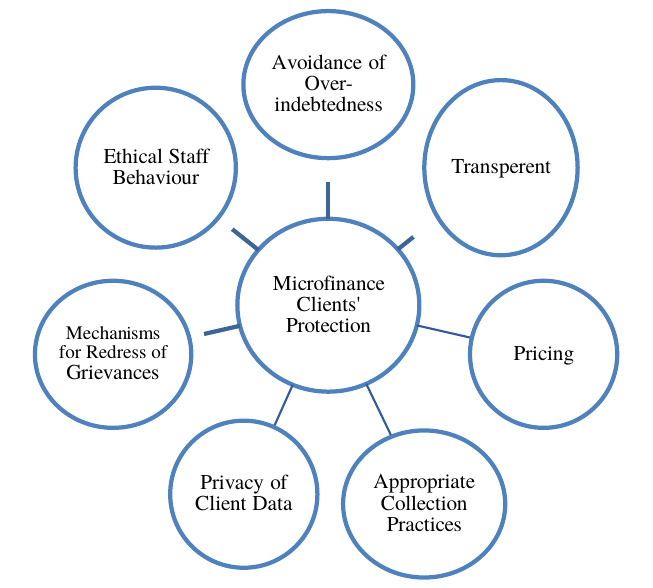

Client protection arises from the imbalance of power, information, and resources between consumers and microfinance service providers, which often places consumers at a disadvantage. At the early stage of microfinance development, protecting clients was not an issue since the sector was relatively small. However, client protection gained wide acceptance in 2008 when the portfolio quality of MFIs began to worsen and most micro-borrowers could not repay their loans (Mader 2013). In response, some governments imposed regulations while key stakeholders such as the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) initiated broad consultations and discussions on the way forward. This led to the development, adoption, and implementation of client protection principles (CPPs) and guidelines aimed at ensuring that providers of financial services accord poor clients fair treatment and protection from harmful financial products. Figure 2 illustrates the key CPPs and the smart campaign[2] is promoting them to protect the interest of clients for sound, social, and financial performance of the sector.

The empirical evidence on the implementation of these principles has remained limited particularly in Africa. While some implementation challenges persist at the organization level, research on client protection in microfinance is yet to gain the needed attention from the research community. This could be due to the fact that microfinance is a relatively new area in development finance and client protection is a recent development concern posed by digitisation of the sector. Further discussion on each CPP is provided in sub-headings below.

Avoidance of over-indebtedness

Over-indebtedness is a serious risk in microfinance, and is defined as ‘the continuous and structural struggle by clients to meet loan repayment deadlines and the undue sacrifices made to honour their loan obligations’ (Schicks 2013, 1239). This means that clients have to forego other basic necessities of life such as food and education for a long period just to enable them to repay their loans. Client over-indebtedness has two dimensions: (i) poor borrowers take credit and are unable to repay, and (ii) lenders supply more credit than borrowers are able to repay due to market competition (Arun and Murinde 2008). This means that MFIs increase the risk of over-indebtedness as they compete for more clients without paying much attention to loan utilisation and monitoring. This can have adverse impacts on clients’ welfare, MFI financial sustainability, and cause reputational damage to stakeholders (governments, donors, investors, and MFIs).

In public administration, over-indebtedness is related to economic, social and personal aspects of the life of individuals and institutions. Schicks (2013), in analysing the repayment behaviours of 531 urban micro-borrowers in Ghana from a consumer protection perspective, found that 30 percent of the clients were over-indebted for various reasons namely: low return on loan investments, use of loans for non-productive purposes, lack of assets, and adverse shocks to borrowers’ financial situation. In addition, personal factors such as borrowers’ financial literacy and multiple borrowing contribute to over-indebtedness (Schicks 2013; McIntosh and Wydick 2005). At the organizational level, internal inefficiencies, unethical operations, and MFI malpractices are key drivers of client over-indebtedness (Hossain 2013). Commercialisation of microfinance (high-interest rates) also plays a role in deepening over-indebtedness. There is need for MFIs to observe careful lending practices. From the viewpoint of administration, simply pushing out loans to clients for the sake of profits without assessing their ability to repay and the suitability of the products offered could lead to industry collapse. However, commercialisation also offers opportunity for MFIs to diversify their funding base, widen their product range, and transform their institutions (Reichert 2018). Deposit mobilisation which is used as a means to reach poor clients and achieve financial sustainability is also part of commercialisation (Al-Azzam 2019). The concept of commercialisation therefore has different interpretations in the literature.

Transparency

Transparency is a strategy to influence an MFI relationship with various stakeholders (Tadele, Roberts, and Whiting 2018). MFI transparency is important for donors, regulators, and the institutions themselves. Both institutional and environmental factors influence MFI transparency. Tadele, Roberts, and Whiting (2018) analysed the impact of ownership structure and macro factors on 223 MFIs transparency across 11 countries in SSA. Using a transparency index developed, the findings revealed low level of MFI transparency. Greater levels of transparency were found to be associated with larger MFIs and NGOs. In the case of NGOs, this could be attributed to the need to attract and sustain donor funding since transparency and accountability matter for these institutions in an effort to deliver the much needed social change. Furthermore, financial sector development and size are significant determinants of MFI transparency. Financial disclosure has a positive effect on MFI performance (Quayes and Joseph 2017).

Pricing

This is related to the products and services offered by MFIs to clients. One key function of MFIs is to satisfy clients’ needs by ensuring that appropriate financial products are developed and delivered to them. Thus, appropriate product design and delivery, appropriate pricing, and terms and conditions, regarding products and services, must be made known and affordable to clients. MFIs are also expected to provide a real, positive return on client deposits. As such, MFIs need to continuously work on their ability to listen to clients’ concerns and factor them into their operations to ensure adequate protection (Forster, Lahaye, and McKeen 2009). At the same time, clients must be properly informed about the specific features of the products available in the market in order for them to make informed choices. This can be done through financial education and consumer protection awareness campaign. The question about whether MFIs undertake product awareness campaign, and how effective this is done in Africa when it is done remains topical. MFIs are therefore expected to design products with clients’ peculiarities in mind.

Foelster, Pierantozzi, and Pistelli (2016) analysed client satisfaction and consumer protection in Peru based on a pilot project that offers mobile technology services to clients. The authors collected data covering five CPPs and reported a high level of satisfaction among clients on MFI products and services. The majority of clients (67%) rated their interaction with loan officers as positive (good relationship), thus suggesting that MFIs are taking consumer protection issues more seriously in product design and relationship management. Previously, Ghate (2007) found that the unattractive features (cap on loan size and long loan cycles) of the self-help group (SHG) model of credit delivery contributed to the microfinance crises in Krishna, India. Cull et al. (2015) in analysing MFI performance reported that client protection and transparent pricing were strongly associated with larger MFI portfolios and average loan size. These studies suggest that institutional factors drive client protection and this has management implications.

Appropriate collection practices

Appropriate loan collection methods need to be employed so that the rights of clients are not violated. MFIs must treat clients fairly and respectfully and avoid all forms of discrimination. In addition, they must ensure adequate safeguards to detect and deal with corrupt, aggressive, and abusive treatment by staff or their agents during loan sales and debt collection processes.

In examining the code of conduct that was promulgated in Krishna district, India, aimed at understanding the kind of consumer protection issues relevant to microfinance, Ghate (2007) found that the drive for MFIs to increase outreach and profitability, high-interest rates, coercive debt collection practices employed by MFIs, and over-lending were the root causes of the crisis. The coercive loan collection process was not only abusive and unethical but also forced some clients to migrate from their homes, hence, the need to regulate microfinance sector.

Privacy of client data

Ensuring the privacy of client data is central to client protection. MFIs are encouraged to respect and maintain the confidentiality of individual client data collected, based on the available laws and regulations. This suggests that the right to receive and use client data must be legally binding on MFIs to prevent abuse and financial malpractices. However, the inability of most MFIs especially the small and unregulated ones to adopt new technologies to help create and manage the database of clients poses serious concerns. Besides the fact that the cost outlay is high, personnel in that field are limited, thereby resulting in supply gap.

Mechanisms for redress of grievances

Mechanisms through which the concerns of clients can be factored into decision-making processes are important for organisational growth. MFIs need to have dedicated units set up solely to respond to the concerns of clients and to factor them into organisational planning. However, little attention has been paid to this principle by financial institutions, and this poses a challenge to the imperative of addressing client complaints (Rutledge 2010). Microfinance clients typically have limited options when it comes to getting their grievances addressed. There is also absence of protective approach by supervisory authorities with regards to establishing and enforcing fair standards for the benefit of consumers.

Ethical staff behaviour

The need for unimpeachable conduct by MFI staff and their agents is critical in ensuring that clients are well protected from any form of abuse and malpractice. MFIs are challenged to ensure that the conduct of their staff or agents is in line with acceptable practices and the rules of behaviour enshrined in organisation’s code of conduct. Theft and fraud by some MFIs in Uganda culminated in a large-scale crises which led to a decline in public trust in the financial sector (Duggan 2016). The unscrupulous activities of opportunistic lenders have implications for MFIs’ reputation and efforts aimed at promoting financial inclusion (Duggan 2016). MFI staff sitting in front of defaulters’ doors, putting up overdue loan notices on defaulters’ doors, and the use of offensive language by MFI staff and group lenders have been documented as some of the ways employed by MFIs to recover loans in India (Ghate 2007).

4.1 Lessons Learned from Selected African Countries

Implementation of CPPs appears to be minimal in Africa though efforts are underway with the SEEP Network currently supporting seven countries[3] on the continent to implement and document outcomes. The lessons shared here are based on available data aggregated from five out of the seven countries focusing efforts on tracking the implementation of CPPs. Not all country reports are currently available.

Data source

The SEEP Network is offering support to countries to track the level of implementation of CPPs and the reports generated from the country level studies are used in this study to provide a broader view on the status of implementation. Individual MFIs, MFI associations and international networks at the country level developed codes of conduct and client protection policies to guide their operations which the SEEP Network study seeks to harmonise and unify. The use of these practitioner reports is then supported by extant literature on the microfinance sector.

For Rwanda, self-assessment of 5 MFIs coupled with a market diagnostic survey, conducted by the Association of Microfinance Institutions in Rwanda (AMIR) was done. A baseline assessment on AMIR’s code of conduct which evaluated members’ understanding and perceived implementation of CPPs was also done as part of the country level study. In Senegal, the study covered 5 MFIs and assessed their compliance with CPP standards between the year 2014 and 2015. In Uganda, the assessment covered 5 MFIs and code of conduct developed by Association of Microfinance Institutions in Uganda (AMFIU) in 2014 aimed at effectively creating a regulatory framework for financial consumer protection. In Burkina Faso, 6 external assessment reports conducted on the sector performance was used together with interactions with 5 MFI staffs. For Benin, 8 focus group discussions (FGD), 1,733 individual interviews with clients and 8 in-depth interviews with MFI managers were conducted in four locations.

Table 1 presents a summary of the level of implementation of CPPs in the selected countries. For appropriate product design and delivery, MFIs are providing relatively diversified products that suit the needs of clients. Despite the broad product mix, concerns over efficient and timely product delivery as well as the mismatch between supply and clients’ needs remain an issue due to the inability of MFIs to collect and incorporate clients’ feedback into product development. Formal systems necessary to ensure appropriate product design and a robust client feedback loop appear to be lacking in most MFIs. For instance, in Senegal and Burkina Faso, collateral seizure often takes place outside of the legal process and this poses a risk to clients. In Uganda, client feedback is sought and valued, but most MFIs do not take advantage of the feedback process to feel the pulse of their clients. In Benin, late repayment of loans increases the likelihood of clients experiencing consumer protection problems (Sanford, Laura, and Wajiha Ahmed 2015). The level of implementation is fair and does not pose risk to clients generally. However, collateral valuation and seizure policies need to be put in place to sanitise the system. Also, MFIs need to conduct systematic client satisfaction surveys to support product development.

Prevention of over-indebtedness is the most challenging principle to implement, particularly for unregulated MFIs. Credit risk (Par 30) is increasing undesirably, and is significantly higher than 10% for some MFIs in Senegal (Behaghel 2015). In Burkina Faso, there is general awareness among MFI managers on the risk of over-indebtedness (De Briey 2016). However, MFIs are doing well in applying standards of repayment capacity analysis and credit bureau usage in Uganda. Greater levels of awareness from a client perspective is needed for improved performance. MFIs should participate more in credit bureaus, build awareness among government agencies, approve loans based on repayment capacity, invest in staff training, and improve internal control systems. Expanding access to affordable credit information to all MFIs and strengthening of local appraisal processes is indispensable. The level of implementation is good as there is clear regulation of credit limits and the use of credit bureau (Behaghel 2015; Brusky 2014)

In addition, while MFIs make efforts to communicate transparently and effectively with clients, issues over incomplete pricing information remain despite regulations governing the disclosure and display of the annual percentage rate. Generally, MFIs do not communicate the total cost of credit and use pricing mechanisms that are confusing (flat and declining) (Brusky 2016; De Briey 2016). Inadequate training of staff is part of the reason for the incomplete information communicated. As such, most clients do not know exactly how much they are paying on loans and are also unable to compare MFI prices. Some MFIs do not explain potential fees to clients. In Senegal and Burkina Faso, clients only receive oral explanations on loan terms and conditions without receiving a copy of the contract prior to signing for informed decision making. The level of implementation is good, but strong efforts are needed to improve disclosure and client understanding of the true cost of products (Behaghel 2015). Further training for staff on the terms and conditions associated with various products and services is critical.

Responsible pricing is critical in microfinance but wide variations exist across MFIs in different countries (Nair 2010). For instance, MFI transparency data for Uganda in 2011 show a wide range of pricing (20-157%) with a weighted average for NGOs (72%), NBFIs (76%), SACCOs (65%) and banks (35%). The use of standardised formula in establishing interest rates is lacking and most MFIs base their pricing decisions on rates charged by their peers. Interest rate caps through regulation (24% in Senegal) are said to weaken financial health of MFIs, especially those located in rural areas posited to be structurally less profitable (Behaghel 2015). The main risks associated with interest rate caps are that rural MFIs could potentially move to urban areas and may increase supplementary fees (Behaghel 2015; Brusky 2014) This could affect poor people living in rural areas who require microfinance services. In Burkina Faso, MFI pricing practices were found to be non-discriminatory with moderate fees and penalty charges (De Briey 2016). The level of implementation is good but more needs to be done in the case of Burkina Faso to improve on MFI efficiency.

Table 1 also revealed that codes of conduct exist in the selected countries for the fair and respectful treatment of clients. Yet, practical implementation remains a challenge since the specific practice conduct is not spelt out. For instance, the code of conduct for the Association of Microfinance Institutions (AMI) in Rwanda clearly defines standards for fair treatment of clients but appropriate collection procedures and MFI-specific policies on staff conduct and sanctions in case of noncompliance do not exist, thereby hampering its effective implementation (Brusky 2016). While abusive staff behaviours have been penalised in Senegal, staff training remains insufficient with limited support systems. In Burkina Faso, most MFIs prefer out-of-court settlement as they employ ethical standards in loan recovery (De Briey 2016). The status of implementation is weak and strong institutional efforts are required by microfinance associations to put the code of conduct into practice. Control mechanisms, imposing penalties and strengthening assess ethics criteria must be sufficiently incorporated into MFI operating procedures and practices. Awareness raising on appropriate loan recovery strategies and dealing respectfully with client defaults needs managements’ consideration (Behaghel 2015).

Confidentiality in the use of clients’ data is a growing area of concern due to the absence of appropriate policies and systems in place. In Senegal and Burkina Faso, clients are not well informed about the use of their personal data, and MFIs generally lack comprehensive privacy policies. However, In Uganda, data security is taken more seriously but disclosure and concrete policies are lacking. The level of implementation is weak and there is a need for MFIs to improve data systems infrastructure, raise awareness of data use and disseminate best practices (Brusky 2014; De Briey 2016).

Mechanisms for complaint resolution are the weakest in the CPPs implementation as highlighted in Table 1. This is attributed largely to the high number of unregulated MFIs[4] that do not have written policies/procedures to deal with grievances. Effective complaint mechanisms are vital in empowering clients and in providing valuable feedback to MFIs on their employees, products, and services. Most MFIs recognise the usefulness of client feedback but are poorly equipped to collect and manage their (clients) grievances. The procedures are not systematised or integrated into the management of activities and as such the mechanisms are inefficient, lack direction, and are not implemented in practice (De Briey 2016). In Senegal and Benin, MFIs generally do not inform clients about the possibility of lodging a complaint internally for potential redress (Behaghel 2015; Sanford, Laura, and Wajiha Ahmed 2015). Complaint handling hotline and internal recourse mechanisms to collect clients’ inputs are some of the ways to deal with the situation. Empowering clients and institutions to get insights into staff behaviour, product, and services are important elements in the complaint-resolution mechanism chain.

5. CHALLENGES FACED IN IMPLEMENTING CLIENT PROTECTION PRINCIPLES

The implementation of client protection principles (CPPs) has received very little attention even though efforts are being made for their adoption and efficient implementation at the MFI level. The institutional structure of most MFIs remains a challenge in ensuring the financial protection of clients (Rutledge 2010). The organisational structures of most MFIs do not have units specifically mandated to oversee consumer protection issues and efforts to do so have remained tokenistic. This suggests that even where MFIs have informed clients, the necessary structures to help them demand their rights do not exist. MFIs also miss the opportunity of collating clients’ concerns and incorporating them into decision making for sustained growth and development.

A conflict exists in most countries as to which agency has oversight responsibility for MFIs, and hence, should enforce the appropriate financial regulations passed for compliance. In some countries, financial supervisory agencies take on consumer protection issues while in others it is the general consumer protection agency that provides oversight responsibility (Armstrong 2008). There is the need for a single agency to handle clients’ complaints and inquiries irrespective of the organisational structure (Rutledge 2010). The inability of MFIs to effectively deal with client complaints can have negative impacts on the development and use of financial products. It is important for MFIs and consumer protection agencies to consolidate customer complaints about financial services annually and publish such statistics to help improve client confidence and transparency in the financial system.

In addition, policies on competition in financial markets are inefficient in promoting client welfare. For competitive markets, policies on competition are sufficient to ensure that firms succeed in their client protection efforts by making the needed products and services available (Armstrong 2008). However, in most microfinance markets in Africa, though competition is fierce and growing, more needs to be done in retail financial markets to ensure efficiency. Fierce competition among MFIs could undermine institutional approaches aimed at protecting clients with negative consequences for the entire sector. Comparable information on pricing, increased awareness of market conditions, and clarification of hidden costs are critical issues that require policy support. Consumer protection agencies need to advocate for policies that prohibit misleading and fraudulent marketing activities by MFIs and enforce them.

Furthermore, the question of how to evaluate the implementation process of the CPPs (for instance over-indebtedness) remains a challenge due to limited clarity and standard measurements. These principles, therefore, appear to be market-specific with limited practical application and evaluation at the industry level. This ambiguity requires further research and policy consultations within the sector.

6. THE WAY FORWARD/ SALIENT STRATEGIES

Key lessons from the review of CPPs implementation and the challenges that come with it provide a firm basis for discussing the way forward. In this regard, a number of proposals and suggestions have been made and are discussed below.

6.1 Dealing with Over-Indebtedness

Reducing client over-indebtedness can be done through financial supervisory agency or consumer protection agency that will strictly monitor MFIs’ loan activities. MFIs themselves and their associations need to build the needed expertise to deal with the technicalities that come with financial service delivery especially loan administration and the avoidance of multiple borrowing. Educating clients to borrow and invest wisely in profitable ventures need to be pursued. Financial institutions should be mandated to register with the supervisory agency and be licensed. Financial service providers must be made to go through well-designed certification programmes to ensure a good understanding of the products and services offered to the public and to promote the interest of clients.

6.2 Pursuing Responsible Finance Strategy

Social responsibility constitutes the ethical concerns that a firm has towards its social obligation and value for the good of society. Responsible finance is the shift in focus by MFIs to take client protection and social performance management issues seriously in their operations. Advancing client protection issues can be achieved through (i) developing client-focused codes of conduct and industry standards; (ii) implementing consumer protection regulation and supervision; and (iii) improving consumer awareness and financial capability (McKeen, Lahaye, and Koning 2011). This means that the involvement and participation of various stakeholders including consumers themselves are central to promoting responsible finance. As pointed out by Nair (2010), microfinance initiatives must take into account their responsibility towards the communities that they serve by seeing clients as key stakeholders and encouraging inclusive participation. There is the need for MFIs to align their decisions with the needs, priorities, and aspirations of clients, and this must be done ethically.

Beyond good quality portfolio management, there is need to include the experiences of micro-borrowers and the sacrifices that they make in planning to help minimise internal risk of debts (Schicks 2013). The continuous demand for loans and strong repayment statistics by MFIs do not guarantee that clients are well protected (Schicks and Rosenberg 2011). There are other mechanisms that need to be put in place by MFIs which will address client protection issues. Pivotal among them is research.

6.3 Improving Consumer Awareness and Financial Education

Insufficient financial literacy skills continue to impede households’ understanding of financial contracts and negotiation with financial institutions. For instance, understanding the risk associated with long-term loans granted in foreign currencies at variable interest rates is an issue for most clients. Improving consumer awareness and financial education are vital tools for promoting client protection. Financial literacy and education are concerned with skills, knowledge and information exchange which manifest in a change in behaviour. However, one critique of financial education based on empirical research is that information transfer alone is not sufficient for effective learning and behavioural change.

The literature on the role of financial education presents mixed findings. Empirical evidence shows that it enhances understanding of insurance contracts and significantly improves basic awareness of financial choices and attitudes of clients towards financial decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell 2009; Cole and Fernando 2008). Contrary evidence shows that financial education does not typically result in a behavioural change in any substantial way and may not be effective and target-specific. Hence, measurement of change in financial behaviour becomes difficult and challenging (Carpena et al. 2011). Such training may not also foster individual abilities to calculate and compare interest returns, insurance costs, and household income and expenses (Lusardi and Mitchell 2009). This suggests that pursuing financial education may or may not lead to improvement in the choices made by clients on financial products. Malra, Mathur, and Rajeev (2015), in evaluating the impact of financial education on development goals, proposed the use of microfinance client awareness index (MCAI) in determining the level of financial awareness of clients. The tool (MCAI) was reported to be useful in analysing clients’ awareness of financial issues. This paper emphasizes the call for its adoption.

Efforts must also be made to help clients understand their legal obligations. This can be achieved by financial institutions’ increasing disclosure and making simple fact sheets available to clients. The terms and conditions of all financial products, services and contracts need to be spelt out and explained in simple plain language. Developing national strategies for financial education is a long-term perspective in dealing with the issue. More focused training in the form of experiential learning, role playing, group-based exercises and radio broadcast is needed to strengthen the rights of consumers and MFI staff. Substantial differences exist in microfinance markets in terms of maturity, depth, regulatory environment and capacity of MFIs, and tailored training programmes should reflect this market-specific context. This could help expose clients to international best practices on CPPs and help MFIs and regulators to better understand client protection issues for effective implementation.

6.4 Enforcement of Regulations and Codes of Conduct

Regulation of MFIs could help in determining the kind of social protection to be provided to clients. Social protection is useful in assisting poor clients to survive in adverse conditions and in promoting a better lifestyle for consumers (Arun and Murinde 2008). There is a need for close engagement between government and MFIs in developing and enforcing the required regulatory legislation. This can be done by giving specific tasks to the regulatory agencies, providing adequate logistics and resources for them to function effectively, and periodic review of legislation passed. Cost-benefit analysis to ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of regulations is necessary. However, a balance must be created between government regulation and market competition since excessive regulation can stifle financial innovation. Regulators should strive for the highest standards of consumer protection without eliminating the beneficial effects of responsible innovation on consumer choice and access to credit (Bernanke 2009). The setting up of regulatory units to oversee consumer protection issues needs consideration and more should be done to ensure compliance.

Microfinance associations at the national levels and MFIs themselves should work more closely and enforce the appropriate codes of conduct using the right mechanisms to help discipline loan officers and sanction unethical behaviour. Setting up a code of conduct on fair pricing by the various central banks to guide microfinance associations undertaking self-regulation is necessary. Countries developing new microfinance laws/regulations could include CPPs and set up a special task force to monitor their effective implementation.

6.5 Supply of Appropriate Products and Services

There is a need for MFIs to provide tailored financial services that adhere to clients’ protection principles (Shinozaki et al. 2017). Also, product adaptation, to meet the needs of borrowers, is extremely important. MFIs need to make their lending rules and guidelines known to potential clients and adhere strictly to their implementation. Undertaking financial consumer research will help MFIs in developing the most suited products for the varied markets.

7. CONCLUSION

The researchers systematically reviewed the implementation of client protection principles (CPPs) in the light of regulation of the microfinance sector in Africa. Discussions and lessons shared are based on data drawn from five countries currently implementing CPPs While efforts are underway across countries to regulate the microfinance sector through the enactment of laws and legislation, challenges still remain in terms of effective implementation of such regulations. The regulatory structure in most countries does not lend much support to the smooth implementation of CPPs. The rapid growth of the microfinance sector has led to increased access to financial products and better livelihoods for the poor. However, the proliferation of unregulated MFIs, poor governance, poor risk management, and multiple borrowing have contributed to client over-indebtedness, making client protection an imperative.

The analysis revealed that only a few studies have empirically analysed the level of implementation of CPPs in Africa following their introduction. While efforts are made by MFIs to implement all the seven principles, client over-indebtedness has received much attention. It is the most challenging to implement due to the absence of operational standards and large unregulated MFIs in some countries. Privacy of client data, mechanisms for complaint resolution, fair and respectful treatment of clients, and transparent pricing are the principles with low achievements in the CPP implementation in Africa. More attention needs to be paid to them at the MFI and policy levels so as to promote client welfare in financial service delivery. Differences in the level of market information exist among actors to the disadvantage of microfinance clients, and some regulations passed do not have clear provisions for client protection. At the MFI level, improving staff training, strengthening client education on data protection, and using multiple channels to address the concerns of clients in a timely and more efficient manner will go a long way in protecting microfinance clients.

More research on the status of implementation of CPPs is needed to support the formulation and passage of regulations with clear focus on protecting microfinance clients. Developing operational standards at the country level to effectively deal with client over-indebtedness needs to be pursued by governments, policymakers and regulators. Regulatory agencies should ensure full adherence to CPPs by MFIs and enforce the appropriate regulations. Future studies should consider analysing the level of CPPs’ implementation by increasing the sample to cover countries not currently supported by the SEEP Network. This could yield useful comparative information in terms of programme impacts and could facilitate future planning. Detailed analysis of ways in which international financial agencies could support national financial consumer protection and education could be explored.

(1) To maintain consumer confidence in the financial system; (2) assure constant supply of services to consumers; (3) to assure that customers receive sufficient information to make good decisions and are dealt with fairly; (4) to assure fair pricing of financial services; (5) to protect consumers from fraud and misrepresentation; and (6) to prevent invidious discrimination against individuals.

A global campaign launched in 2009 to seek support for the adoption and implementation of client protection principles and guidelines in the microfinance sector.

Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Rwanda, Senegal, and Uganda.

For instance, In Uganda, AMFIU members constitute 80% of the estimated microfinance clients out of which majority (97%) of the association ordinary members belong to non-regulated MFIs.