1. INTRODUCTION

At the time of the Meiji Restoration in Japan (1868), a family with the surname “Kato” resided in a village in Tochigi prefecture—their main business was moneylending. The Kato family expanded its business, and mainly through moneylending, accumulated more than 50 hectares of land by the end of the Meiji Era.

This study aims to analyze the lending activities of the Kato for a 32-year period (1874–1905) based on their books and notes, and thereby clarify the features of informal moneylending in a village in Meiji Japan. Simultaneously, we intend to show the outcomes of the family’s long-term lending activities, such as their accumulation of land and provision of funds for local development.

As is well known, modernization in Japan started with the implementation of several reforms during the Meiji Restoration. Among these, the Land Tax Reform implemented in 1873 was one of the most important (Hayami 1991). Until this reform, agricultural land transactions were officially not allowed. The new land system introduced freedom of land transactions, and as a consequence, land could be used as collateral for mortgage loans. At the same time, as the name of the reform indicates, the aim of the new land system was to secure stable national revenue through land taxes. This system led to an excessively heavy tax burden on farmers. Farmers frequently borrowed money from various sources for tax payments. In the case of lending collateralized by land, failure to repay the borrowed money resulted in the surrender of the land to the moneylender. The land reforms might have led to modern and efficient financial transaction, but this reform set the background for the concentration of agricultural land with a smaller number of people, creating a seriously biased landholding structure.

The above-mentioned points are well-known stylized facts. Many papers on Japanese economic history have already highlighted the formation of the Japanese landlord system in the Meiji Era (Crawcour 1997; Hayami 1991; Sakane 2010; Teruoka 2008). Therefore, adding one more related case may not be a contribution to the existing literature. However, not many studies have discussed the features and outcomes of long-term informal moneylending in the context of microfinance. It is meaningful to elucidate missing aspects of a discussion of microfinance by using long-term microdata from the supply side. In particular, we want to emphasize that increasing access to modern finance does not always lead to improvement of the economic welfare of the poor.

The following are the three specific issues we explore in this study. First, we describe the features of informal moneylending in rural Meiji Japan, where human mobility was severely restricted[1]. Rural society at that time was an isolated world. The villagers knew each other very well and collaborated in daily activities. In such societies, there were no problems triggered by so-called information asymmetry. The Kato family, whose activities are the main object of analysis in this study, had lived in the village for many generations. They knew in detail the contents of the villagers’ wallets as well as their characters. There was no lending risk associated with a sudden flight from the village; moral hazard or adverse selection was not likely in such a closed village. Lenders did not charge very high interest rates, since their business assumed the existence of poor borrowers. Occasionally, they even assisted their customers by using many methods, because lenders and their borrowers had to coexist. Thus, the two factions had a kind of mutually dependent relationship. It is interesting to examine how this informal moneylending worked under such condition.

Second, we study the long-term changes in moneylending activities, including changes in the lending conditions, purposes of loans, and effects on local financial markets. In particular, we describe the shift in moneylending to new areas.

The third point we highlight is associated with the impact of microfinance. Discussions in the literature on microfinance center on how the provision of financial services improve the borrowers’ welfare, especially the welfare of the poor (Armendáriz and Morduch 2010, 268). However, researchers have not discussed the effects of the provision of financial services on asset distribution or income structure. This study aims to fill this gap through an analysis of informal moneylending over three generations, clarifying its long-term effect on the distribution of agricultural land, one of the most important production factors.

The strong point of this paper lies in our discussion by using a moneylender’s microdata[2]. We employed the data from the books and notes of the Kato family. Although some data were missing for several years, the data was reliable with detailed figures for about three decades. Not many studies have analyzed financial activities spread over more than 30 years using such high-quality data.

2. FEATURES OF RESEARCH SITE AND DATA

The Kato family had lived in Nabatame village for long. The village, located around 100 km north of Tokyo, belonged to Tochigi prefecture. Like other villages at the time, the village was an administrative unit at the grassroots level; it had a budget, and a council that discussed its budgeting, management of public education, infrastructure construction, sanitation, and so on. Mashiko village, famous for pottery production, is located in the northern area adjoining Nabatame[3]. The pottery business of Mashiko influenced the village economy of Nabatame, as we show later.

The main agricultural products of Nabatame village were cereals. According to the village data kept in the Kato shed, there were 54 farm households in 1874, and the households produced 80, 33, 10, and 8 tons of paddy, barley, wheat, and soybeans, respectively, in the year. Only 4 tons of paddy and 2 tons of soybeans were sold outside the village, indicating that the village’s agriculture was largely subsistence oriented. Fish fertilizers were brought into the village in the mid-18th century. In the 19th century, fertilizers were traded using river transportation, and one of fertilizer traders was Goemon Kato, the head of the Kato family.

Yaheita Kato, the grandson of Goemon, was the head of the Kato at the time of the Meiji Restoration. The Kurobane clan appointed him as an officer responsible for agricultural promotion and products storage for the area covering his village. At the beginning of the Meiji Era, Yaheita and Tsunesaburo (son-in-law of Yaheita) undertook financial activities. Around 1879, Yaheita handed over the position of household head to Tsunesaburo, and Yaheita concentrated on his independent business. In 1891, Tsunesaburo passed away unexpectedly, and his son, Masashi, inherited the family assets and business. The next year, Yaheita also transferred his assets to Masashi, who took over the entire family business with his grandfather’s assistance.

The main sources of data analyzed in this study are the books and related notes of the Kato family. The Kato had two kinds of books, daily records of lending and recovery, and year-end records of assets and debts[4]. The above three persons described lending and other activities with written records by themselves. However, Tsunesaburo’s records on assets are incomplete, containing only the data of outstanding lending for 1877 and 1884–1887. Due to this constraint, analysis on assets changes of the family for 1874-1892 used the data only from Yaheita. Concerning the analysis on lending situation, we pick up three years, i.e., 1877, 1886, and 1905. For the former two years, data by Yaheita and Tsunesaburo is available. For the analysis of lending situation in 1905, data from Masashi is used.

3. ECONOMIC BACKGROUND

3.1 Meiji Restoration and the Land Tax Reform

After the Meiji Restoration, the new government implemented a series of reforms, abolishing the social ranking system, affording freedom of residence area selection, and allowing freedom of job selection. For farmers, these measures allowed the free choice of crops and facilitated land transactions. Beginning in 1873, the government implemented the Land Tax Reform, confirming the locations of plots of land, measuring the plots, and determining their owners. Besides, the government evaluated each plot of land according to its land productivity. The initial tax rates were determined as three percent of the estimated land value. In addition, a local tax equal to one-third of the land tax was imposed on farmers.

Farmers had to pay their land tax in cash, not in kind. Further, the estimated value of land for tax calculation was fixed. Hence, the burden on farmers was heavier during periods of deflation. As we explain later, during the Matsukata Deflation period, many farmers could not pay their land tax and therefore had to relinquish their land.

After the Land Tax Reform, many farmers rose in rebellion against the new government. The government reduced the tax rate to 2.5 percent. However, following the military buildup after the Sino-Japanese War and during the Russo-Japanese War, the government raised the tax rate to 3.3 percent, 4.3 percent, and 5.5 percent in 1899, 1904, and 1905, respectively. As a result, the average tax burden per household in terms of total land tax (national plus local taxes) increased from 12.1 yen in 1892 to 38.6 yen in 1905 (Toyo Keizai Shimposya 1926). Thus, during the period of our analysis, farmers suffered from increasing land tax.

The Land Tax Reform implemented the modern land system by clarifying the tenets of landownership and rights of landowners. After the Reform, landholders received title deeds to their land, and financial transactions involving land mortgage—including land pawning—were institutionalized. Thus, the Reform entailed the legalization of formerly informal land transactions. Prior to the Meiji Era, de facto land transactions, land leasing, and property transfers were common, although not allowed officially. People in need of money widely resorted to land pawning, by which the right of land use and duty of tax payment were transferred to the money provider. However, if the borrower so desired, he/she could continue cultivation on the pawned land through tenancy. If the borrower could not repay the money, in principle, the pawned land could be disposed of. Before the Meiji Era, the repayment period was usually rescheduled, and the borrowers could buy back the pawned land even after the repayment due date. We refer to this point again[5].

3.2 Agricultural situation

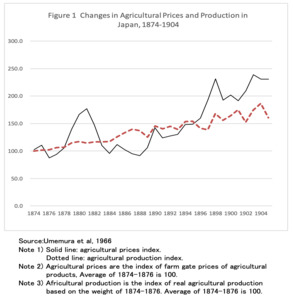

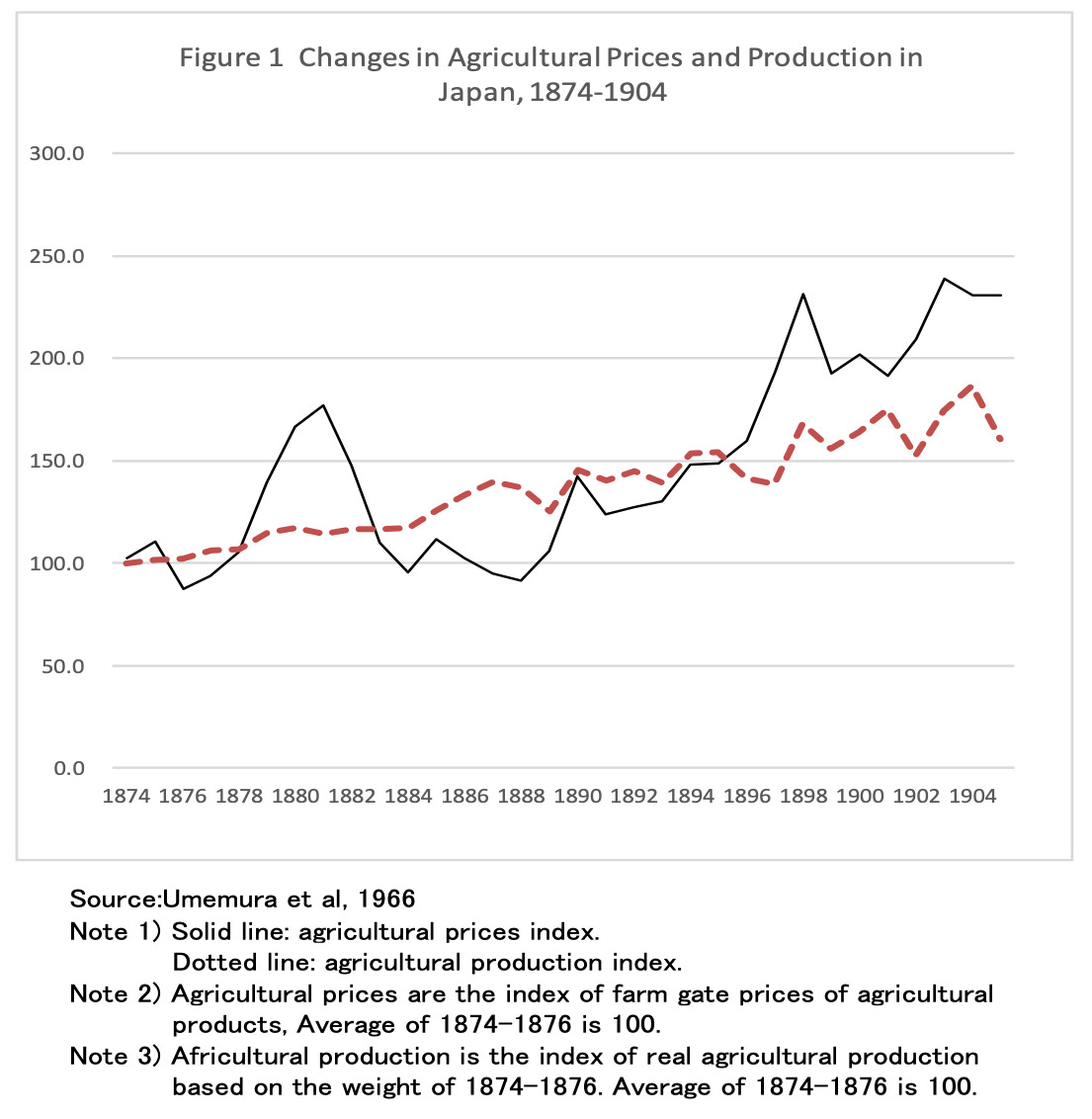

It could be better to explain a village’s agricultural situation by using the data on that village; however, the statistics on agricultural prices and production of the village are incomplete. Here we use the estimated agricultural data for Japan based by the group of Kazushi Ohkawa (Umemura et al. 1966), assuming that changes in the agricultural economy of Nabatame village roughly corresponded with the national trends.

First, the real agricultural production during 1874–1905 grew at an annual rate of 1.87 percent, indicating a good performance (Yamada, 1991). When we divide the whole period into four sub periods of equal duration (eight years), the growth rates of the earliest two sub periods were more than two percent but of the latter two sub periods were -0.04 percent and 0.75 percent, respectively, indicating a slowdown.

Second, the average annual growth rate of agricultural prices was 2.63 percent, suggesting mild inflation. Investigating the detailed changes in prices, we found a rising trend with cyclical variation. The most important point noted is the price rise from 1876 to 1881, and then, after 1881, the deflation occurred in reaction. The price rise was due to the civil war (1877). The increased wartime budget needs caused the government to adopt an expansionary fiscal policy. On the other hand, after the war, the government immediately introduced a tightening policy, which caused serious deflation called as “Matsukata Deflation”. During that deflationary period (1881–1885)[6], many farmers were unable to pay land tax, and lost their land. This occurred all over Japan (Ishii 1991; Nakamura 1983), as exemplified by the cases in Nabatame village.

4. EXPANSION OF NET ASSETS OF THE KATO FAMILY

4.1 Changes in net assets of the Kato family: An overview

First, we present an overview of changes in net assets of the Kato family. We obtained the figures[7]for 1874–1892 from Yaheita’s accounts and for 1893 onward from Masashi’s books. The household heads themselves wrote those books, aiming to summarize their year-end figures. However, following bookkeeping delays, the figures written were not always those at the end of the year. In Tsunesaburo’s asset data, the outstanding amounts lent were available for only three years (1878, 1884, and 1886). Hence, we cannot directly compare the pre-1892 figures in Table 1 with the post-1893 figures. The assets of the Kato family before 1892 shown in Table 1 are underestimated, since the table does not include Tsunesaburo’s assets.

Table 1 shows that Yaheita’s net assets totaled 2,394 yen[8] in 1874 and grew to 17,748 yen by February 1892. The lending amounts reported by Tsunesaburo were 3,500 yen at the end of 1877, and 5,300–5,600 yen during 1884–1887. From these figures, the net assets of the Kato family is around 7,000 yen in 1877, which grew to 20,000 yen during 1890–1891. Masashi’s net assets were 24,000 yen in 1893 and 73,000 yen in 1905. This figure of 1905 is more than 10 times of the corresponding figure in 1874, although the comparison is in nominal terms.

In terms of nominal growth rate (calculated by regression analysis), the average annual growth rate of Yaheita’s net assets was 15.1 percent during 1874–1883, but this declined to 7.7 percent during 1884–1892. Concerning Masashi’s net assets, the average annual growth rate was 10.2 percent during 1893–1899 and 8.3 percent for the remaining years. Thus, in spite of a decreasing growth rate, the assets of the Kato family as a whole grew at an impressively high rate throughout the analysis period.

4.2 Changes in composition of net assets of the Kato

From Table 1, we can discuss the changes in the Kato family’s net asset composition. The following three points about changes in the asset composition are noteworthy.

First, the Kato family’s total borrowings were very small. At the end of 1874, their borrowing was 5.2 percent of their total net assets. In 1893, when Masashi streamlined the business, the borrowings of the Kato family were negligible. This means that the funds for the family’s lending came mostly from its accumulated money. The funds structure of the Kato family was quite different from that of contemporary microfinance institutions[9].

Second, at the starting year of our analysis (1874), the share of lending in total net assets was 94 percent, and the share of money provision through pawn broking was 11 percent. The amount of money provision via pawn broking increased to 671 yen by the end of 1876 and to 1,262 yen (14 percent in total net assets) by July 1884. Around 1884, there were notable changes in their lending business. During 1884–1886, the amount lent declined sharply, while the value of the obtained land increased rapidly. Provision of money via pawn broking peaked in 1884, but from 1886 onward, that figure did not appear in the books, suggesting important changes in the family’s lending business. The increase in landholding suggests that they obtained land mainly via disposal of mortgaged and pawned land of their borrowers.

The changes in the Kato family’s asset composition around the period 1884–1888 reflect the difficulties in the moneylending business caused by the Matsukata Deflation. Agricultural prices dropped 46 percent from their peak in 1884 (Figure 1). Farmers’ debts increased significantly because of the fixed land tax, and overdue payments became the norm of the day. From July 1884 to February 1886, Yaheita took steps to dispose of his problematic loans, including those collateralized with pawned items. He transferred the titles of mortgaged and pawned land to his name, rescheduled loans to accept principal amount repayments without interest, and extended the repayment periods of defaulters. As a result, the share of land in the Kato family’s net assets increased significantly. The Kato family’s business changed from moneylending to a combination of land management and moneylending.

Third, notwithstanding the difficulties caused by the Matsukata Deflation, the family’s lending business did not decline. Their outstanding lending amount began to increase in 1889, and reached the milestone level of 20,000 yen in 1899. Moreover, the Kato family’s financial business apparently became diversified, having general lending, special loans with favorable conditions, money provision to small enterprises in the Mashiko pottery business, and investment in stocks and public bonds. In 1907, the Kato family had two pillars of business, moneylending and land management, and owned 57 hectares of land in the village.

4.3 Withdrawal from pawn broking

For the first-half period of his lending activities, Yaheita’s business performed well, as indicated by the high growth rate of his net assets. Land tax was indeed high, but agricultural production was expanding, and agricultural prices were also rising. The demand for money started to grow, and the supply of money through moneylending and pawn broking became a good business in line with the increasing demand. However, the Matsukata Deflation changed the business landscape drastically. One prominent change in Yaheita’s business was his withdrawal from pawn broking business.

As already mentioned, land transactions were not allowed by law in the early Edo period (1643). If farmers needed money, they would pawn their land to get money. In pawn financing, if a borrower does not repay the money, the lender usually rescheduled loan repayment. The borrower can get back the pawned land by paying the borrowed money even after the due date[10]. However, this procedure was not favorable to lenders. In 1742, the transfer of land to pawnbrokers was legalized, with a maximum “buyback period” of 20 years. If the borrower could not repay the money lent within 20 years, the lender could confiscate the pawned land. Thus, the Edo shogunate accepted restricted land transfer in the case of land pawning.

However, even in the Meiji Era, the acquisition of money via land pawning continued in accordance with the “pawned land return custom.” In case of moneylending by the Kato, land pawn broking was an important and easy measure for providing money.

With respect to the case of land pawn broking, we provide one related information. In 11 cases of land pawn broking by the Kato in 1883 and 1884, the average amount of money disbursed was 30 percent bigger than the official value of the pawned land. This means that the pawned land did not serve as an effective security, having only symbolic meaning in the financial transaction. Based on a judgment that borrowers offered their most important asset and that they would make every effort to repay the money, the lender provided 30 percent more money than the value of the pawned land.

When agricultural prices sharply declined at the time of Matsukata Deflation, the Kato family faced many cases of default. The family decided to address the problem of default through waivers, rescheduling, and disposal of pawned land. After this decision, the Kato changed its loan policy, determining the loan amount within the value of the mortgaged land. During the six years 1886–1891, the ratio of the average loan amount to the value of pawned land was 0.86. The Kato family made its lending policy more stringent after the disorder caused by the Matsukata Deflation.

On the other hand, farmers who wanted to use money in a more modernized manner were likely to prefer mortgage loans to land pawning. In such cases, farmers could continue cultivating their land. Besides, some farmers tried to obtain money by land disposal using “land buyback” contracts (20 percent of the Kato family’s land transactions were this type of contracts)[11]. Land buyback contracts guaranteed that the seller could buy back the sold land in the near future at the same price as the sale price. In times of inflation, such types of contracts were very beneficial for land sellers, since they could buy back the land at a cheaper rate than the prevailing market price. Conversely, land transactions under such contracts were unfavorable for land buyers (i.e., moneylenders) but the Kato family accepted this as a concession to borrowers. The family respected the long-continuing village customs, trying to maintain its relationships with the borrowers.

5. DETAILS OF LENDING OF THE KATO FAMILY[12]

5.1 Lending situation in 1877

Table 2 shows the lending position of the Kato family in 1877. Note that in addition to Yaheita’s notes, Tsunesaburo’s book is also available in the year. Table 2 indicated the annual interest rates for in-kind lending and land rent in terms of percentage of disbursed money for pawned land. Land rent was regarded as interest on money disbursed through pawn broking.

The lending areas of Yaheita and Tsunesaburo tended to be separate. In Yaheita’s moneylending, the share of loans cases outside the village was over 70 percent. On the other hand, more than half (51 percent) of Tsunesaburo’s lending was within the village. Yaheita’s tendency to lend outside the village becomes more apparent when we examine the share of lending amount. The share of total outstanding amount of Yaheita’s lending outside the village was 92 percent. The average amount they lent per case was 28.4 yen (excluding in-kind lending of rice for consumption), and the amount lent to Mashiko and its pottery-related business is notable. With respect to Tsunesaburo’s lending, the majority of his loans (88 percent) were for less than 25 yen, and the average loan size was only 14.4 yen.

Thus, the father and son undertook lending activities differently, implying that the Kato family responded to the diversified demands of both the village and the neighboring areas. Yaheita’s lending outside the village came from his experience in working with the Kurobane clan as an agriculture-promoting officer. Yaheita established a personal network with merchants, rich farmers, and pottery producers. The network led him to expand his lending activities outside the village. On the other hand, Tsunesaburo provided more micro loans. Actually, Tsunesaburo lent loans for a variety of purposes, such as medical expenses, funerals, temporary borrowing for repayment, paddy transplantation, in-kind borrowing of rice for consumption, money for travel, and so on.

With respect to lending interest, the Kato family applied simple interest[13]. If borrowers could not repay the interest, the unpaid interests were added to the principal, and the certificate of loan was rewritten.

The annual lending interest rates varied from zero to more than 30 percent, but the most common rates were 20 percent and 25 percent. For Yaheita’s lending, the most typical interest rate was 24 percent. For loans less than 25 yen, the interest rates could exceed 30 percent, whereas for loans more than 50 yen, the interest rates tended to be below 20 percent. Yaheita offered favorable interest rates (i.e., less than 20 percent) mostly for the relatively large loans to Mashiko pottery-related business. He had a loan program called “Special Loans” meant for small pottery producers, usually without interest. Tsunesaburo sometimes offered concessional loans to the villagers of Nabatame and other neighboring areas except Mashiko, demonstrating flexibility and special treatment in moneylending. By 1877, the Kato family’s moneylending was going on smoothly, with a yearly return of around 20 percent[14]. This high return was the powerful engine for the growth of the family’s assets.

5.2 Lending situation in 1886

Table 3 shows the distribution of lending interest rates around 1886. Yaheita’s lending consisted of outstanding general loans (141 cases, 3,168 yen) in January 1887, whereas Tsunesaburo’s lending consisted of newly issued loans (139 cases, 1,867 yen) in 1886. Small-sized loans were dominant in Yaheita’s moneylending (108 cases, 77 percent). This trend was interrupted by the disruption in business caused by the Matsukata Deflation. However, the majority of loans in terms of value went outside the village.

Tsunesaburo’s loans were mostly small-sized, and they predominantly went to the villagers. Of his loans, 83 out of 139 (1,113 yen of the total 1,867 yen loaned) were within the village. The number of loans for less than 25 yen was 109 (87 percent), suggesting that microloans were the predominant type issued by Tsunesaburo. However, in this year, lending to Mashiko pottery-related business became significant, with 47 loan cases (34 percent) and a total amount of 531 yen (28 percent).

The interest rate of most of the loans was 20 percent; 104 (74 percent) of Yaheita’s loan cases and 111 (80 percent) of Tsunesaburo’s were at this rate. The interest rates of the remaining cases were 15 percent or lower, and it is hard to find cases with interest rates higher than this rate. Yaheita occasionally applied lower interest rates, especially to Mashiko-related businesses, and Tsunesaburo did not charge any interest in 18 cases, including 10 cases of in-kind rice lending.

Concerning the repayment period and collateral in Kato’s lending, information relating to 260 cases of lending by Tsunesaburo during 1885–1886 offers several interesting facts. First, with respect to the repayment period, most of the loans were for short terms, ranging from less than one month to one year. Pottery producers especially tended to use short-term loans. However, even if the repayment period was short, there were a significant number of cases with unchanged year-end balances. This implies that although borrowers did not repay the principal by the due date, the Kato family did not force them to repay the principal as long as the interests were paid regularly. Second, surprisingly, a majority of the loans by Tsunesaburo were collateral-free. Loans were secured by land and mobile assets such as horses, cereals, furniture, and clothes constituted only 15 percent of the 260 loans Of the collateral-free loans, 74 percent were for amounts less than 10 yen (typically, less than five yen)[15]. Thus, the Kato provided microloans without collaterals, simply receiving written certificates (sometimes writing down only in memos). The family avoided troublesome procedures related to collateral requirements. In the case of mortgage lending, the borrowers and lenders usually went to the office of the district chief and received the official seal on the written documents. The records of the contract were kept in the village office[16]. This was a troublesome procedure, and for micro lending, the Kato family had simple and convenient ways of executing contracts without requiring collaterals. Further, most of the interest rates were 20 percent, as explained in the previous section, and the rates did not change even if collateral was required.

5.3 Lending situation in 1905

Table 4 shows the details of the loans provided by Masashi in 1905. More than half of the cases in total lending were those within the old village. However, if we calculate the amount of loans, only 12 percent was to the borrowers there. The remaining 88 percent of loans were offered to people outside the village.

Thus, lending outside the old village became critical to the business of the Kato family. As seen in the previous section, in the 1890s, lending to Mashiko pottery-related business became significant. Following this trend, in 1905 loans to borrowers in other villages became more important.

In the year, 31 borrowers received loans of which size was more than 400 yen. Among them, nine borrowers had loans amounting to over 1,000 yen. The borrowers of big amounts were merchants, manufacturers, and rich farmers. They were people of good reputation with land assets of 500–3,000 yen, and they usually held respectable positions in the village administration. Concerning pottery-related business, 26 persons borrowed from the Kato, of which nine had loans amounting to more than 400 yen. In all, 60 families among the Mashiko pottery producers borrowed from the Kato family, suggesting that without finance from the Kato, the Mashiko pottery industry would not have been as prosperous.

In 1905, the outstanding amount of money lent by the Kato family reached 41,882 yen (see Table 2). Four years later, Masashi invested his money in the newly established local bank (Mashiko Bank) to become its executive director[17].

5.4 Long-term changes in the Kato family’s lending business

First, during the whole period, the Kato provided around half of loan cases to people within the village; however, in the lending values more than 70 percent was outside the village from the starting year of the analysis. The share of lending outside the village tended to increase[18]. The Kato family tried to finance emerging business in Mashiko and other areas in order to utilize their funds optimally. This lending strategy was an outcome of Yaheita’s experience as an officer responsible for economic development in the area.

Second, the average loan size increased along with the share of loans issued outside the village. Especially during 1886–1905, the average loan size tripled (from 22 to 65 yen), reflecting the expansion of larger-sized loans.

Third, the lending interest rates showed a downward trend. The average annual lending interest rates of the Kato were 22 percent, 18 percent, and 14 percent in 1877, 1886, and 1905, respectively. Similar declines in lending interest rates in the informal sector were found in other areas of Japan, suggesting an increasing linkage between interest rates in the formal and informal sectors[19].

Fourth, the features of the Kato family’s lending were different from those of the exploitative informal moneylenders. Although there were several moneylenders in Nabatame, the Kato family was the most influential in the local financial market. The Kato family could have behaved as a monopolistic moneylender, but the family did not maximize their potential returns from their lending business. There are several lines of evidence for this behavior. As Table 1 indicates, the outstanding amount of lending to relatives and high-ranking persons previously positioned in the Kurobane clan did not change for several years. This implies that the Kato family did not force them to repay their debts. Besides, for around 20 percent of the land transactions, the Kato family accepted the attachment of land buyback contracts. This contract type was not beneficial to the lender; however, considering the economic difficulties of the borrowers and the reputation within the community, the Kato family adopted tolerant policies. Besides, the family provided special interest-free loans to Mashiko pottery-related business as a form of contribution to the economic development of the area (see Tables 4 and 5)[20].

6. MONEYLENDING AND LAND ACCUMULATION

6.1 Changes in landholding structure

Table 6 shows the changes in landholdings (including forestry land) of 56 households in Nabatame village in 1878, 1887, and 1907. The data for 1878 is available from the village records of “Values of Cultivated Land,” and the figures for 1907 were obtained from the records in Masashi’s ledger. The figures for 1887 were calculated from the 1878 data and the annual land title transfers kept in the village records.

In the table, we needed to use one special treatment in calculating the land area owned by households, since household separation may have serious effects on intertemporal comparison of owned land. In countries such as China and Vietnam, which practice apportioned property inheritance, the landholdings of rural households become smaller over generations. In Japan, the eldest-son inheritance system was widely used, and, hence, the effects of property inheritance on the landholdings of rural households were not very serious. However, in Nabatame, there were several cases of household separation (19 estimated cases during the analysis period). In order to avoid the effects of household separation in our analysis, the household’s total owned land is assumed to the sum of the land of the separated households. For example, if household A is divided into households A’ and B in year T, we regard the owned land of household A as the sum of the owned land of households A’ and B in year T. Thus, we obtain the changes caused solely by land transactions, excluding the effects of property inheritance.

Column 2 in Table 6 reveals the wealth rankings. The village office created these rankings in 1873 based on the tax payment levels. These wealth rankings were correlated with the levels of land assets (excluding forestry land). The Kato family, having the first rank in terms of wealth, had 24 hectares of land. In 1878, the land distribution was not equal, but still 37 households owned more than 1 hectare of land. Just after the Land Tax Reform, Nabatame was predominantly a village of owner farmers. After the Matsukata Deflation, many farmers lost their land titles and became tenant farmers. Consequently, the Kato family expanded its landholdings, growing into a large landlord owning 57 hectares. The households 2, 3, and 4 in the table were at second wealth ranking had grown into midsized landlords. On the other hand, other rural households mostly reduced their landholdings.

The Gini coefficient, an indicator of unequal distribution, had values of 0.728, 0.780, and 0.868 in 1878, 1887, and 1907, respectively. The top four households’ shares in total village landholdings were 26 percent, 33 percent, and 53 percent in those years, respectively. Thus, the distribution of owned land became seriously skewed over time.

According to Table 7, the total transacted land during 1878–1907 was 85.7 hectares. The Kato family’s landholdings increased by 34.6 hectares and reduced by 1.3, implying a net increase of 33.2 hectares. The second-, third-, and fourth-largest property holders increased their landholdings in that period (net increase: 11.8 hectares). The landholdings of households other than the four largest property holders (52 households) increased by 23.4 hectares and reduced by 53.1, implying a net decrease of 29.7 hectares.

6.2 Meaning of land accumulation for the Kato Family

In order to discuss the economic meaning of land accumulation for the Kato family, we assess the rate of return of released/purchased land. The rate of return of land increase is defined roughly as the ratio of total land rent minus total tax (land tax and other related taxes) divided by the price of land. We calculated the rates of return for 27 land transfers of Yaheita from July 1883 to May 1887 and for 23 transfers of Tsunesaburo from January 1883 to June 1887. The rates of return ranged from 6 to 19 percent for Yaheita’s business (average: 11.6 percent), and from 9 to 17 percent for Tsunesaburo’s (average: 13.2 percent)[21]. We calculated these figures using land leasing contracts; hence, the actual ex-post rates would be lower than the estimates. Assisted by Yaheita’s memos, we can calculate the rates of land rent paid to land prices. The results of these calculations indicate average rates of 8.4 percent in 1887, and 6.9 percent in 1888, reflecting the declining prices of agricultural products.

As discussed, the lending interest rates of the Kato family centered around 20 percent (i.e., from 20 percent to 24 percent) in 1877, and the ex-post rate of return on lending was around 20 percent. In 1886, just after the disposal of several bad loans, most interest rates were 20 percent; the ex-post rates of return of moneylending were 13.1 percent in 1886 and 18.4 percent in 1887[22]. In 1886, the lending situation slightly changed due to the disorder caused by the Matsukata Deflation, but as of 1887, the Kato family’s moneylending business was recovering, normalizing to its pre-disorder level. These calculations indicate that the profitability of land purchase was far below that of moneylending. Thus, land accumulation was not a desirable result for the Kato family.

In addition, landholding was sometimes unstable, because of the land buyback custom. Even after the completion of land registration, land sellers could buy back the sold land after several years by repaying the principal. The Kato family bought 29.8 hectares of land usable for cultivation or housing and 23.3 hectares of forestry land, whereas they sold 7.2 and 1.5 hectares respectively of those land types during 1888–1918.

The land buyback custom had a negative influence on the effective use of productive resources, because the ambiguity of land ownership caused difficulties in land improvement. Consequently, cases of land sell back decreased gradually. However, the Kato family had to accept this kind of contracts until the end of the 19th century, and it took another 20 years for them to close those contracts.

7. CONCLUSIONS

For over 32 years, the Kato family’s moneylending activities changed dynamically in response to the overall economic situation, and significantly influenced the local economy. We now summarize the features of the family’s moneylending and the outcomes of that lending by explaining the three specific issues referred to in the Introduction section.

First, the Kato family’s moneylending was completely different from the classic image of exploitative moneylenders (Robinson 2001, p.178-180). One notable difference lies in the level of lending rates. The maximum lending rate of the Kato family was 25 percent—much lower than the rates listed in Robinson’s table (Robinson 2001, 199-201), or the rates of informal moneylenders in the textbook The Economics of Microfinance (134 percent to 159 percent, 60 percent, and 70 percent in Punjab, Thailand, and Pakistan, respectively; Armendáriz and Morduch 2010, 32). This statement is valid even when we calculate the real interest rates after deducting the inflation rates. In addition, the Kato had several concessional and flexible lending practices such as interest- and collateral-free lending.

The following four factors significantly influenced the Kato family to set relatively low lending interest rates and adopt concessional lending policies: (1) The Kato family could fully utilize their information accumulated over many generations. The area was a small closed society, where people knew each other. There was no problem of the so-called information asymmetry. There were no recorded instances of intentional default, since it was almost impossible for borrowers to escape from a debt burden precipitately. (2) The lenders and borrowers were mutually dependent; this situation allowed them to avoid extremely severe lending conditions. (3) The risks were secured, except for micro lending, by collateralized land (including land pawning) or inventories of pottery products (in the case of Mashiko pottery-related business). (4) The Kato family had a strong reputation in the area, having members with experience as the village and district heads. The Kato family must have behaved as a respected leader in the area.

Second, the Kato family’s moneylending practices changed dynamically. Initially, micro lending and money provision to neighboring areas served diverse purposes. The share of micro lending decreased gradually, whereas the share of business loans increased and the loan sizes became larger. Lending interest rates also declined gradually, reflecting a closer linkage with the general financial market. These changes were the results of the Kato family’s response to changes in demand. It would not have been possible for the family to attain an average annual growth rate of more than 10 percent if it had concentrated only on the village demand. They had to expand the scope of their business beyond the old village if they wanted to use the accumulated funds optimally. One paper has demonstrated that Mujin Kous (ROSCAs) in Japan transformed into Mujin companies, and then into mutual banks during the long-term process of economic development (Izumida 1992); further, the logic for the transformation of informal finance is similar to that for the long-term changes in the Kato family’s lending business.

It is interesting to note that the family provided interest-free loans to Mashiko pottery-related business. Concessional loans with favorable conditions have been criticized seriously as “subsidized credits” from the standpoint of sustainability (Adams, Graham, and Von Pischke 1984) In the Meiji era, however, informal lenders provided subsidized credit in a natural manner. This finding is important in the controversy on the roles of subsidies, and the roles should be reconsidered in accordance with the East Asian experiences on rural finance. The Kato family used their profits from general lending to provide special concessional loans (so-called cross-subsidization), and they did not face any problem with business sustainability.

Third, as a result of long-term moneylending activities, the village’s land distribution became increasingly skewed. Borrowers could alleviate their economic difficulties by using temporary credit, but finally they lost their land to bad mortgages, and as a result, land ownership in the village became concentrated in the hands of a few families. The economic gap between the rich and the poor widened through financial intermediation. The Kato family expanded its land ownership within the village during 1878–1907. Around half of land acquisition (65 percent in 1893 and 49 percent in 1904) was through financial transactions.

We recognize that land accumulation by moneylenders was not the impact caused by financial considerations alone. From the standpoint of rigorous impact analysis using the Difference in Difference (DID) or Randomized Control Trial (RCT) approaches (Armendáriz and Morduch 2010, 267–75; Karlan and Goldberg 2011), may interpret the increasing gap in landholdings between moneylenders and tenant farmers differently. Even if the government did not legalized mortgage financing, a similar situation in asset holdings would have occurred. However, it is a historical fact that financial transactions caused biased landholding in Japan[23]. Modernizing the financial system under particular economic and social conditions created a biased landholding structure[24]; and we must consider this historical fact serious when analyzing the impact of microfinance.

We need to add one more thing related to the impact of loan. Investigating financial transactions between the Kato and the villagers, it becomes evident that the recipients sometimes used the borrowed money for their daily needs (consumption smoothing by finance). However, if borrowers continue this kind of borrowing, it could lead them to a more miserable situation. We cannot simply celebrate the expanding access of the poor to financial services: Finance is a double-edged sword, and under certain conditions, financing can bring users to a more serious situation.

One of important features of the studied village was the low household mobility. In 1878, there were 56 households in the village. Until 1908, only five households left the village whereas two households moved in. Thus, apparently, the village formed an isolated society.

It is not easy to obtain high-quality financial data in low-income countries. Recently, methods to obtain microdata on poor people through financial diaries have received attention (Collins et al. 2009). In this study, we used data from the moneylender’s books and memos; these data were financial diaries from the supply side. Several papers from Japan have analyzed the long-term activities of moneylenders by using this type of financial diaries. See Fukuyama 1978, Kase 1985, and Shibuya 2000.

Pottery production in Mashiko started in 1852, and the products were shipping to the Tokyo metropolitan area. In 1877, Mashiko was a large village consisting of 239 households. In 1889, Nabatame village was merged with four neighboring villages to form the new Mashiko village. In 1894, the village was renamed Mashiko town.

Yaheita called the former “Book on Inflow and Outflow of Money” and the latter “Book on Profits and Losses of Assets,” whereas Tsunesaburo called the former “Note on Inflow and Outflow of Money” and the latter “Book on Inquiry of Money Lending,” or “Main Book on Money Lending.” These books and memos are available at the Tochigi Prefecture Archive Office.

Steel et al. 1997, mentioned, “It is much easier for a landlord-lender to make productive use of pledged farmland indefinitely than for a bank to seize it” (p.822). Similar events occurred in the Edo and early Meiji periods in Japan, when land transactions and land title transfers were seriously constrained.

With regard to the Matsukata Deflation period, we follow the specification of the period as "1881–85,"following the research by Ishii 1991.

All figures in this paper are in nominal terms, as written in the books and notes of the Kato family.

It is difficult to estimate the present value of one yen in 1874, but very roughly, it would be equivalent to 8,155 yen in 2009, using the long-term indexes of agricultural prices (Umemura et al. 1966) and MAFF as deflators. Consequently, one yen in 1874 would be equivalent to 87 dollars in 2009.

The Kato family accepted money as deposits from several wealthy women wanting to put their extra money to good use, but the amount was small. In the context of discussions on microfinance, the provision of savings facilities is very important for microfinance. See Armendáriz and Morduch 2010, Collins et al. 2009, and Vogel 1984. However, the provision of financial services without savings can work under some conditions, as in the case of the Kato family.

This custom of “pawned land return custom” by historians.

After land transactions were legalized, the “pawned land return custom” became a “land buyback custom” in some areas.

For the methods of money provision including lending and pawn broking of the Kato family, see the appendix table.

In the contracts, they wrote the interest per 12 yen to make it easier to determine the monthly payment amount for one year.

As illustrated in the case in 1878, Yaheita’s interest revenue was 611 yen (from his book on land rent and interest revenue), and the outstanding amount of general lending was 3,038 yen. By using these figures, we calculate the annual rate of lending return as 20.1 percent.

Tsunesaburo usually did not require cosigners for micro lending within Nabatame village. However, in cases of mortgage lending, he always required cosigners.

Adams and Fitchett (1992, 2) defined informal finance as “all financial transactions, loans, and deposits occurring outside the regulation of a central monetary authority or financial monetary authority.” In this sense, the lending activities of the Kato family are categorized as “informal.” However, the lending activities using land as mortgage were authorized publicly, as explained in the text, and subsequently their main activities were not underground transactions.

In 1924, Mashiko town had three large landlords including the Kato. The total amount of outstanding lending by these three families exceeded that of the Mashiko bank.

Similar phenomena occurred in the lending business of the Nishihattori during 1892–1914 in Okayama prefecture (Kase 1985).

Shibuya (2000) indicated that the average lending interest rates of the Sakurai and Ishigaki families in Tohoku area were considerably high and set at arbitrary levels in 1880. However, those rates later trended downward and showed stronger linkages with the lending interest rates of local banks. Declines in lending interest rates were common in many places in Japan at the time.

From 1900, Masashi reduced the number of special interest-free loans to Mashiko pottery-related business. In Table 6, there is no column for these interest-free special loans. The Kato family had changed its lending strategy by reducing the provision of special concessional loans in favor of the expansion of ordinary loans.

In-kind land rent was converted into value terms following Tsunesaburo’s memo in 1886. Land rent and other taxes were calculated as four percent of land values, following Yaheita’s memo.

These figures were obtained by calculating the ratio of interest revenue (330 yen in 1886 and 582 yen in 1887) to the outstanding amount of general lending at the beginning of the year (Table 2).

See Sakane 2010, 273-276. According to Tanaka (1978, 103-104), the national average ratio of rented land in 1873 was around 30 percent; this had risen to 40 percent during 1887–1892.

The “dark side of microfinance” (Hulme 2007) exists in many places where micro lending is practiced.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)